今年夏天雨水特别多,全国各地普遍降雨量比较大。不论对老城区还是新城市来说,这些雨水都是个挑战。许多城市因降雨出现内涝,开启了“看海模式”。这背后,有许多悲惨而无奈的故事。城市雨水管理逐步成为了一个关系到人民群众生命财产安全的重大问题,也逐步成为大家关注的热点。鉴于此,记者采访了亚洲开发银行东亚区域开发部城市发展专家Kristina N. Katich,希望能找到大家关注的问题的答案。

Kristina N. Katich的专业研究领域是气候适应性城市。去年在珠海举办的 “第十届中国城镇水务发展国际研讨会与新技术设备博览会”上,她曾做了题为《推进中国城市雨水管理》的发言。今天,她将以国际视角,通过成功的案例,从政策、技术、前景等方面分析探讨雨水管理的未来。

(左一:Kristina N. Katich)

记者:您从何时开始城市雨水管理研究的?在您的职业生涯中,有没有遇到过让您印象深刻的事?可否和我们分享您的故事?

Kristina N. Katich: 有趣的是,我工作在城市雨水管理领域是因为我对整体规划与社会公平感兴趣。起初,我学习建筑,因为我感觉建筑有其内在的社会和实用价值——创造美丽、有用、安全的空间。随着职业的发展,我转向了城镇环境规划与管理,也就开始了灾难管理与城市雨水管理。对我个人来讲,我不太喜欢防洪的硬派工程;渠化、涵洞、堤坝会破坏维护城镇环境的自然进程。这些技术把洪水的风险转移到了抵御洪水能力更差的下游社区,却把大量快速流动的洪水涌向那里。相反,我更喜欢尽可能多的采用软工程的办法,因为基于环境和景观的洪水管理可以在很多方面极大的有益于城市。尽管我总是喜欢基于自然的方案,我对 “日光”的办法,即打开20世纪七八十年代铺设、下挖的水道,以形成自然的城镇水道很感兴趣。我的研究生论文研究的是气候适应性城市,我研究了首尔的昌溪川项目。除了辅助城市雨水管理,这个项目通过建立公园,使城市更具活力。尽管开始当地居民反对,这个项目不仅大大的改善了生活环境,也提高了当地的土地价值。该项目已获得国际认可,并被认定为最佳范例广泛在美国等国家采用。

记者:在您看来,城市雨水管理的最终目标是什么?为了达到这一目标,需要哪些方面共同努力?

Kristina N. Katich:城市雨水管理的最终目标是确保所有的居民——富人、穷人、年轻人、老年人——每个人都有一个安全的环境。城市开发尊重环境并与自然环境共生很重要。亚洲的很多快速开发的城市忽略了低劣规划的基础设施对自然环境的影响,随着时间的推移,这些影响将挑战城市的可持续发展。铺装路面、管道化城市河流意味着城区吸收的雨水越来越少。正如我之前谈到的,这增加了下游洪水泛滥的风险,同时也危及城市水供给,通过地面沉降破坏建筑物的基础;世界上的城市,例如墨西哥城、雅加达、北京,因为铺装路面阻止了含水层的回水,正在慢慢的下沉。

有许多案例,低劣规划的城镇化以及城市雨水管理给无法承受洪水的物理、经济影响的贫穷地区造成不必要的负担。例如,洪水泛滥地区或边缘地区的土地、建筑成本可能更低,导致穷人聚集在这些地区。洪水来临的时候,他们不仅可能失去家园、财产,他们的安全都将会有危险。

城镇雨水管理有三大障碍。一是洪水并不认行政区的边界,上游活动极大的影响着下游的社区。这将导致城市间协作以及城镇开发、雨水管理的基础设施和实践的管理变得困难。另外,这也导致行政层面的雨水管理融资变得困难。

第二,同一个城市内,政府机构间的协作通常很差。许多政府机构的行为——包括环境保护、应急管理、固体废物管理、交通、城市开发等等——将会影响城市的抗洪能力。政府机构间通常有不清晰、重叠的职责,缺乏理解和信息共享。

最后,不是每天可见的问题,政客们也没有兴趣去改进。除非一个城市近期经历了洪水,城市雨水管理通常在政府的日程中处于较低的优先级——尤其是在官员变更频繁的国家和城市。许多政府愿意构建居民一年365天可见的基础设施;雨水管理设施大都在地下,而且施工对居民交通和日常生活也有影响。除非有大量降雨或者河水泛滥,雨水管理设施的投资会被忽视或者被低估。城市雨水管理需要协作、资金、综合规划、以及构建安全、环境友好的城镇环境的远见。

记者:城市建设对雨水自然循环有哪些影响?如何实现人和自然的和谐管理?

Kristina N. Katich:城镇建设的形式和速度对雨水自然循环有巨大的影响。在中国,城镇规划通常没有包含足够多的雨水管理规范。许多城市开发较快,有向外扩张而不是增加密度的趋势。城市开发增加了不透水路面,减少了储存区,从而增加了城市地区的径流。

为服务原有地区设计的排水系统无法承受从新铺装地区聚集的多余雨水。上游地区新增的雨水充满了下游现有的管道,导致雨水无处可去。

随着城市的扩张,原来农村或城市周边的河流变成了市内河流。这样,由于淤积、城市废物管理较差导致的垃圾,以及新建筑、高架、桥梁的占用,这些河流的排水量和蓄水能力会降低。高强度的土地开发,改变了周围的自然地形地貌,改变了河流系统、河漫滩、湖泊的自然流动。

这就是海绵城市的概念在中国如此重要的原因之一。海绵城市试点将展示投资基于生态设计的雨水管理应该应用于中国所有的城市。西方知名的“绿色设施”、“低影响开发(LID)”,基本原则是减少人工系统,如排水管道、泵站的开发和建设,对自然和生态系统的影响。低影响开发旨在通过储存,渗透,蒸发,保留,减少地表径流,模拟自然生态环境,以增加地下水补给。通过去中心化、小范围源头控制机制和相关技术,减少由暴雨导致的径流。目的是尽可能多的维护开发前的自然环境和水生态循环。

记者:在城市雨水管理领域,世界上有哪些城市做的比较好,有哪些经验可以学习和借鉴?

Kristina N. Katich:我最近刚从荷兰回来,荷兰的水管理经验给我留下了深刻的印象。众所周知,荷兰通过堤坝、堤岸的使用,开垦大片土地,以及传统荷兰风车的使用,在管理他们的国家与海洋的关系方面有着悠久的历史。不那么广为人知的是,这个国家本质上是默兹河、莱茵河、斯海尔德河冲积的大三角洲。另外,超过80%的人口住在城市里,有很高的年均降水,城市雨水管理、控制河面高度以防止洪水泛滥极其重要。

雨水管理最有创意的是鹿特丹。位于莱茵河与默兹河的三角洲地带,鹿特丹采取了积极的总体规划管理,不仅使他们免于洪水灾害,而且免于受到潜在的气候变化的影响。通常,气候变化不仅会影响降雨的频率,而且会影响降雨的密度。气候变化对本地的影响已经被感知,但是很少有城市有应对潜在影响的意愿和资源。从2013年开始,鹿特丹有了自己的气候适应策略:找出当地脆弱点,创建用于未来弹性规划和投资的框架。

意识到传统的抗洪措施不足以应对未来的风险,鹿特丹开始尝试其他办法,收集并疏导雨水以防地区泛洪。鹿特丹的干预从小规模——例如支持绿色屋顶、雨水收集的开发——到大规模,例如重新设计现有的堤坝,用作多种用途。

鹿特丹减少洪水风险的创新项目,例如Benthemplein水上广场,已经赢得众多国际城市规划师的认可。集成了公共娱乐空间、温室、蓄水,Benthemplein水上广场是世界上第一个大规模的水广场。有不同座位、活动场所的多层次空间,广场在降雨量大的时候,成为了水库。宽阔的排水沟收集雨水,并导向公园的深层盆地。盆地会24小时吸收雨水;超大降雨的时候,吸收的雨水会被抽到附近的水道,从而减轻鹿特丹污水处理系统的负担。公园包含大量的绿色空间和公共空间,可用于运动和社交活动,给周边带来了生机,很受本地学生和居民的欢迎。

总的来说,我认为鹿特丹可以作为中国城市雨水管理学习的一个极佳范例,不仅是因为鹿特丹应对风险的整体气候适应性规划,而且是因为它集成了像绿色屋顶这样小规模尝试。城市重新吸收的每一滴雨水对当地以及下游的防洪都有影响。

记者:夏日来临,雨水增多,中国很多城市下了暴雨,有些地区甚至下了冰雹。暴雨对城市排水系统是一个挑战。在城市排水防涝方面,有哪些行之有效的应对措施?

Kristina N. Katich:中国最明显的一大问题是大多数城市只有小型或者管道排水系统。在许多国家,雨水系统通常包括小型系统和大型系统。小型系统用于应对不密集的雨水,设计应对2到10年一遇的暴雨。小型系统通常包括地下管道和沟渠。另一方面,大型系统用于应对严重的暴雨,设计应对50到100年一遇的暴雨。大型系统通常包括旁路通道,绿化带和道路,用来处理超过小型排水系统处理能力的径流。2012年,亚洲开发银行和住建部支持的一项中国城市雨水管理研究表明,这是中国城市最薄弱的问题之一(http://www.adb.org/projects/45512-001/main)。这项研究找出了一些优秀城市示例,例如亚洲的吉隆坡,以及一些西方城市。

在吉隆坡,一个“智能通道”被用作多种用途。通道是直径为12米的三层结构。最底层用于通常降水时的径流排放。中间层平时用于交通,在暴雨的时候,会关闭交通,改为排水通道;设计应对5年以上一遇的暴雨。在特大暴雨的时候,最上层以及整个通道会关闭交通,完全用于排水。

来源: http://www.tunnelvisions.eu/projects/nieuwe-pagina/

中国已经通过了一系列的法规,将改进并鼓励城市排水和城市防洪设施的建设,并且引进了海绵城市的概念。

记者:最近在雨水管理方面,是否出现了新的材料、设备、最新科技产品,能够大大提升雨水管理的效率?

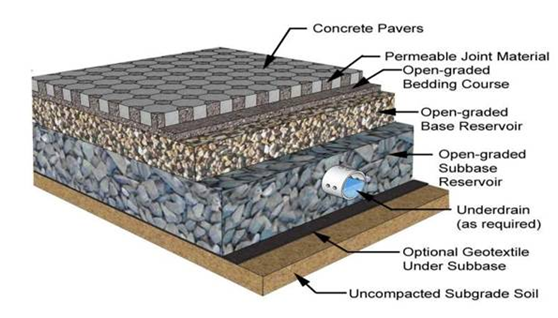

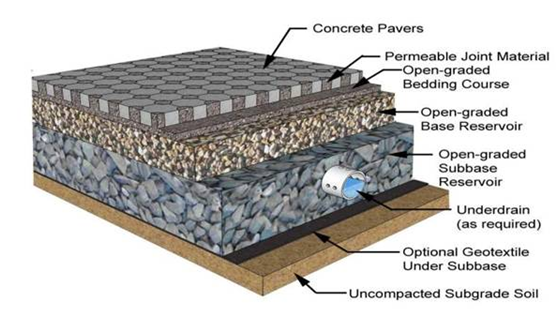

Kristina N. Katich:雨水管理最明显的技术更新可以从透水路面的演变看出来。过去的几年,这一领域有了突飞猛进的进展。过去,透水路面意味着铺石头或路砖的时候,留有空隙,让水可以渗入。这种办法在小范围内有效。现在,许多透水路面更复杂,有多层,不仅吸收水,而且过滤,导向附近的沼泽或者水道,因此减少了排水和污水处理的负担。透水路面种类和复杂程度不同,给开发人员和管理者在预算范围内,满足设计要求的更多的选择。透水路面可以减少径流,防止水体淤积,控制污染物,同时可以和铺装地区的树木共存。

记者:最后,请问您对有志于从事雨水管理领域的人员有哪些建议?或者您有哪些话想对中国读者说?

Kristina N. Katich:对任何有志于从事雨水管理,以及中国的读者,我鼓励他们在低影响开发以及基于自然的城市排水解决方案方面学习。气候变化将会导致更频繁更密集的降雨,将会超过亚洲城市现有的已疲于应对的降雨量。哪怕城市没有采取有效的措施,个人依然有能力通过参与雨水收集、绿色屋顶、低仰角绿化带贡献自己的力量。最终,多个个体的贡献将会在城市防洪中发挥重大作用。

我们感谢Kristina N. Katich和我们分享雨水管理领域的经验和看法,首尔的昌溪川项目、鹿特丹的Benthemplein水上广场、吉隆坡的“智能通道”,都给我们留下了深刻的印象。先进的透水路面设计,正印证着“科学技术是第一生产力”,改变着城市雨水管理与规划的未来。先进的理念,先进的技术,加上我们无数雨水管理领域内孜孜以求的工作者,相信我们的雨水管理会做得更好,相信我们的城市会更好。

Interview Outline

Kristina N. Katich

Urban Development Specialist,

East Asia Regional Department (EARD)

Asian Development Bank

Field of Study: Climate adaptation and cities

Interview theme: Urban Storm Water Management

(1st left:Kristina N. Katich)

1. When did you start your study in urban storm water management? There might be something or some technology that impressed you very much in your career, could you share your story with us?

Interestingly, I came to work on urban storm water management out of an interest in holistic planning and social equity. Initially, I trained as an architect, as I felt that architecture had inherent social and utilitarian values – the function to create beautiful, functional, and safe spaces. As my career developed, I moved on to urban and environmental planning and management, which ultimately led the issues of disaster risk and urban storm water management. Personally, I am less of a fan of hard engineering approaches to prevent flooding; channelization, culverts, and dams tend to disrupt the natural processes which are required to maintain the urban environment. These techniques pass the flooding risks to downstream communities which may have even less capacity to absorb and cope with large amounts of fast-moving water. Rather, I prefer to use soft-engineering approaches as often as possible, as environmental and landscape-based flood management can greatly benefit cities in a variety of ways. While I have always preferred nature-based solutions, I was particularly impressed with the practice of, “daylighting,” or the opening up of natural urban waterways which were previously paved over or culverted during the 1970s and 1980s. My graduate school thesis focused on climate adaptation in cities, and through this, I learned of the Cheong Gye Cheon Project in Seoul. In addition to helping manage urban storm water, the project also revitalized the heart of the city through the creation of a public park. Despite initial resistance from area residents, the project has greatly improved not only their living environment but also increased local land-values. The project has gained international recognition and is considered a best-practice which is now being adopted in other countries, such as the United States.

Source: http://inhabitat.com/how-the-cheonggyecheon-river-urban-design-restored-the-green-heart-of-seoul/

(many additional photos available on this website)

2. In your point of view, what’s the finalpurpose of urban storm water management? In order to accomplish this, what parties should be involved and what effort should be devoted?

The final purpose of urban storm water management is to ensure a safe and secure urban environment for all residents – rich, poor, young, old – everyone. It is important that urban development respects and considers its symbiosis with the natural environment. Rapid urban development in many Asian cities has neglected the impact that poorly planned infrastructure has had on the natural environment, and overtime, this neglect is challenging the sustainability of cities. The paving of roads and culverting of urban rivers means that less and less rain water can be reabsorbed in urban areas. As I mentioned before, this increases flood risks downstream, but also threatens the urban water supply and undermines the foundations of buildings through land subsidence;cities around the world, such as Mexico City, Jakarta, and Beijing, are slowly sinking because paved roads prevent water from recharging urban aquifers.

In many cases, poorly planned urbanization and stormwater management practices create an unnecessary burden of poorer communities which cannot absorb the possible physical and economic impacts of floods. For example, land and construction prices may be cheaper in flood- or land slide-prone areas, leading them to live in these areas. In the case of flooding, not only could they lose their home and belongings, but their safety and livelihood could be at risk.

There are three huge obstacles to urban storm water management. One is that flooding does not recognize municipal boundaries, and upstream activities hugely affect downstream communities. This can make it difficult for cities to coordinate with each other and other levels of government on urban development and storm water management infrastructure and practices. Additionally, this can make financing storm water management investments very difficult at the municipal level. Secondly, even within cities, there is often poor coordination between government agencies. The individual activities of many agencies – including environmental protection, emergency management, solid waste management, transport, urban development, and others – can affect a city’s ability cope with flood risk. There are often unclear and overlapping responsibilities as well as a lack of understanding and information sharing between agencies. Finally, there is a lack of political will to improve a problem which isn’t visible every day. Unless a city has recently experienced significant urban floods, urban storm water management is usually low on a government’s agenda – particularly in countries or cities with short political cycles. Many governments prefer to build infrastructure that is visible to its citizens 365 days a year; urban storm water infrastructure is largely underground and its construction can be problematic for traffic and other daily activities of city residents. Unless there is a large rainfall or river flooding event, the investment in hard urban storm water infrastructure will go unnoticed and unappreciated. Urban storm water management requires coordination, financing, comprehensive planning, and a vision at creating a safe and environmentally-friendly urban environment.

3. How can urban construction affect natural cycling of storm water? How to accomplish harmonious management between people and nature?

The type and speed of urban construction can have a huge effect on the natural cycling of storm water. In the People’s Republic of China (PRC), urban planning has frequently not included sufficient storm water provisions. Many cities have developed quickly, with a tendency to expand outward rather than by increasing density. City development increases impervious pavement and decreases storage areas, resulting in increased runoff in urban areas.

Drainage systems that were designed to meet the needs of the original service areas are unable to carry extra storm water runoff from newly paved areas in the catchment area. The increase of storm water from the newly developed areas in upstream areas overloads the existing pipelines downstream, leaving storm water with no place to go.

As cities expand outward, rivers that used to be in rural or peri-urban areas become urban rivers. With this, the water-carrying and storage capacity of these rivers decreases due to siltation and possibly garbage if the city has poor solid waste management, as well as the encroachment of development, namely buildings, highways, and bridges. High intensity land development changes the surrounding natural terrain and topography, and alters the natural flows of river systems, floodplains, and lakes.

This is one reason that the Sponge City concept that is being pursued in the PRC is so important. The Sponge City pilots will hopefully demonstrate that investment in ecologically-designed storm water management practices should be used in all Chinese cities. Known as “Green Infrastructure” or “Low Impact Development” (LID) in Western countries, the basic principle is to minimize the impacts on natural and ecological systems caused the development and construction of artificial systems, such as drainage channels and pumping stations. LID aims to simulate natural ecological conditions through the storage, infiltration, evaporation, retention, and reduction of surface runoff, thereby increasing groundwater replenishment. LID minimizes runoff and nonpoint source pollution (NPS) caused by rainstorms by using decentralized and small-scale source control mechanisms and appropriate technologies. The objective is to maintain, as much as possible, the pre-development conditions of the natural environment and hydrological cycle.

4. In the field of urban storm water management, are there any cities that have made great progress?Are there any useful experiences that we could learn from?

I recently returned from a trip to the Netherlands and I was very impressed by the Dutch experiences in water management. It is well known that the Netherlands has a long history in managing the relationship that their country has with the sea, reclaiming large areas of land through the use of dikes, levees, and the traditional Dutch windmills. What is less widely known is that the country is essentially a large delta for the rivers Meuse, Rhine, and Scheldt. Additionally, over 80% of the population is urban and the country has a high average yearly rainfall rate, making it very important for Dutch cities to manage storm water and river levels to prevent flooding.

Of the cities with the most aspirational approach to their storm water management is Rotterdam. Located in the delta of the Rhine and Meuse Rivers, Rotterdam has taken a very active and holistic approach to managing their vulnerabilities to not only flooding by also the potential climate change impacts. Under most models, climate change will affect not only the frequency, but also the intensity of rainfall events. The impacts of climate change on local weather patterns are already being felt, but few cities have had the political will and resources to plan for the potential impacts. Since 2013, Rotterdam has had its own climate adaptation strategy which required the identification of local vulnerabilities and created a framework for future resilience planning and investments.

Recognizing that the city’s traditional flood defenses as being inadequate for future risks, the city began to access other ways to collect and channel storm water to prevent localized flooding. The interventions in Rotterdam range from small scale – such as supporting the development and planting of green roofs and rainwater harvesting– to large scale, such as the redesigning of their existing dikes to allow for multipurpose uses.

Innovative projects related to reducing flood risks in Rotterdam, such as the Benthemplein water plaza, have gained global recognition among urban planners. Integrating public recreational space, greenery, and water storage, Benthemplein water plaza was the world’s first large-scale water square. A multi-level space with different seating and activity areas, the plaza becomes a water reservoir during heavy rains. Wide gutters collect rain water and funnel it towards the deeper basins of the park for collection. The basins allow for the rainwater to be reabsorbed into the ground over a 24-hour period; in cases of extreme rain events, the water is drained to a nearby water way, thereby reducing the load on Rotterdam’s sewage system.The park with its substantial greenspaces and public spaces for sports and socializing has revitalized the area around it and become popular with local students and residents.

Overall, I think that Rotterdam serves at an excellent example of storm water management for cities in the PRC, not only for their holistic climate-aware approach to risk, but also for the integration of small scale efforts such as green roofs. Every drop of water that is reabsorbed in the city can have an impact on local and downstream flood prevention.

5. When summer comes, the rain increases. Recently, it rained heavily in several cities in China, even hail in some district. The torrent rain is a challenge to the drainage system.Are there any effective strategies in drainage and flood prevention?

One of the significant problems in the PRC is that most cities have only minor, or pipeline drainage systems. In many countries, stormwater systems are typically comprised of both minor and major systems. The minor systems are designed to discharge less intensive rainstorms with a design return period of two to ten years. The minor systems commonly consist of underground pipes and ditches. On the other hand, major systems are designed for severe rainstorms with a design return period of 50 to 100 years. Major systems commonly include bypass tunnels, greenbelts, and roads which are used to handle the runoff which exceeds the capacity of the minor drainage system. In 2012, the Asian Development Bank supported a study with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development on urban storm water management in the PRC which identified this as being one of the biggest weaknesses of Chinese cities (http://www.adb.org/projects/45512-001/main) . The study identified a number of good examples in Asia such as Kuala Lumpur, and as well as many Western cities.

In Kuala Lumpur, a “Smart Tunnel” was constructed with multiple uses. The tunnel is a three-level structure of 12m diameter. The lower compartment is used for discharging runoff during normal rainstorms. The middle compartment is used for traffic in ordinary times and will be closed and utilized as a drainage tunnel in rainstorm events with a five-year return period and above. The upper deck and the whole tunnel will be fully closed from traffic in case of extreme rainstorms for discharge of stormwater.

Source: http://www.tunnelvisions.eu/projects/nieuwe-pagina/

The PRC has since enforced a number of new regulations which will improve and encourage the construction of urban drainage and urban flood-protection facilities, as well as introducing the sponge-city concept.

6. Recently, are there any new materials, devices, or latest technologies which could improve storm water management dramatically?

Some of the most significant technological advances related to storm water management can be seen in the evolution of permeable pavements. Over the past few years, this field has grown significantly. In the past, permeable pavement signified the placement of stones or pavers with gaps between them to allow water to filter through, which works well on a small scale. Now many permeable pavements are more complex, featuring multiple layers which serve to not only absorb water, but also filter and convey it to swales or other nearby waterways, thereby avoiding the overloading of storm drains and sewers. The variety and complexity of permeable pavements vary, giving developers and governments more options to find options within their budget to fit their design requirements. Permeable paving has been shown to reduce run-off, prevent siltation in water bodies, control pollutants, and allow the root systems of urban trees to coexist thrive within paved areas.

7. Finally, do you have any advice to those who are willing to start their career in storm water management? Or anything you would like to say to the Chinese audience?

For anyone interested in starting a career in storm water management, as well as for the Chinese audience, I would encourage them to educate themselves on the concepts of low impact development and nature-based solutions to urban drainage. Climate change will bring more frequent and potential more intense rainfall, which will surpass the rainfall levels that already cripple Asian cities. Even if cities fail to take action, individuals still have the capacity to do their part by engaging is activities such as rainwater harvesting, green roofs, and low-elevation greenbelts. At the end of the day, many individual actions can make a big difference to prevent urban flooding.

编辑:赵凡

版权声明:

凡注明来源为“中国水网/中国固废网/中国大气网“的所有内容,包括但不限于文字、图表、音频视频等,版权均属E20环境平台所有,如有转载,请注明来源和作者。E20环境平台保留责任追究的权利。

媒体合作请联系:李女士 010-88480317